No puzzle from me this week, but here’s a nice gentle one from Jaspa on MyCrossword. My crash course on how to do cryptic puzzles begins here.

There’s a brief passage in a 15th century treatise called “Myroure of Oure Ladye” in which an abbot is confronted by a foul, misshapen demon named Titivillus. When the abbot summons up enough courage to ask this guy what his deal is, Titivillus gamely replies:

I am a poure dyuel [poor devil], and my name ys Tytyuyllus, and I do myne offyce that is commytted vnto me: I muste eche day brynge my master a thousande pokes [sacks] full of faylynges, & of neglygences [failings and negligences] in syllables and wordes, that ar done in youre order in redynge and in syngynge [reading and singing], and else I must be sore beten.

Put into plain English, Titivillus’s job is to go around collecting typos and verbal slip-ups until he reaches his quota (a thousand pokes!), lest he be beaten by the Devil himself. He goes on to explain that the Devil wants these typos to keep in some infernal spreadsheet as evidence against their perpetrators when the day eventually comes to process their souls for the afterlife.

Thus ye maye se, that though suche faylynges be sone [soon] forgotten of them that make them; yet the fende [fiend] forgetteth them not.

Since Titivillus’s first appearance on the scene (in 1285), many noble heroes have arisen to do battle with him, from Saint John Bosco (the patron saint of editors) to Ralph Gorin (who programmed the first spell-checker) to Clippy, that peerless paragon of pedantic paperclips. But despite their best efforts, the poure dyuel has been racking up the victories (and filling up his pokes) for seven and a half centuries now, so I’d like to take a moment to give the guy his due and celebrate a few of his greatest finds.

1. The Wicked Bible

In 1631, the royal printer in London, Robert Barker, published an edition of the King James Bible that would come to be known as the Wicked Bible (or the Sinners’ Bible). This shockingly naughty bible contains two typographical errors that are shameful, blasphemous, and deeply funny.

The first, an omission of an absolutely crucial “not” in Exodus 20:14, rendered the fairly important 7th Commandment as “Thou shalt commit adultery,” giving unearned encouragement to a whole generation of fornicators and philanderers.

The second major error (evidently the whole thing was riddled with typos) made an absolute hash out of Deuteronomy 5:24, rendering the phrase “Behold, the Lord our God hath shewed us his glory and his greatness” as

“Behold, the Lord our God hath shewed us his glory and his great-asse.”

In what may be the greatest loss to history since the burning of the Library at Alexandria, there are no surviving copies of the Wicked Bible containing this second error (though three copies have a suspicious inkblot where the error is reported to have been). But you can be certain that Titivillus has an unblemished edition on his bookshelf.

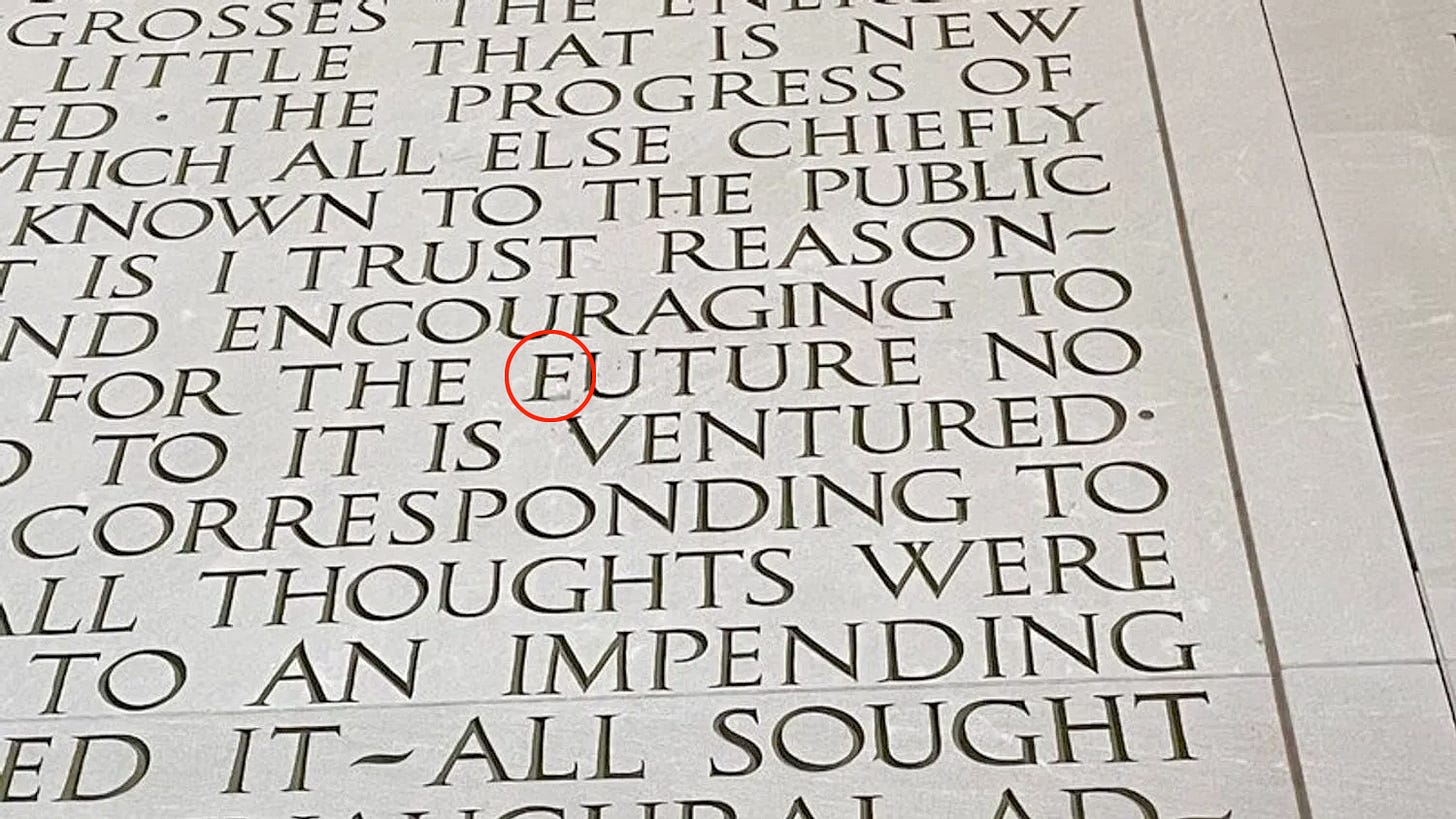

2. The Monumental Error

The engraver of the Lincoln Memorial mistook an “f” for an “e” and chiseled a line from Lincoln’s second inaugural address as “With high hope for the euture, no prediction in regard to it is ventured.” This isn’t nearly as funny as the adultery or the great ass, but Titivillus holds typos that are engraved on a $3 million national monument particularly close to his heart.

3. Everyone Named Cedric

There’s no easy way to say this, but if your name is Cedric, your name is … wrong. But it’s wrong in a cool way!

Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe is a preposterously influential 19th century novel about knights and ladies in the middle ages doing derring do (as one does) and also kissing (thanks, English Literature degree!). As the novel begins, we learn that our hero, Wilfred of Ivanhoe, has been disinherited by his father, Cedric of Rotherwood, because of politics and stuff.

Scott’s influence over our modern fantasies about the middle ages (jousting, Robin Hood, etc.) is profound, but as much as he introduced a Romantic gloss to the period, he also did some real historical research, including for his character names, which are drawn from real figures of the time. This includes Cedric of Rotherwood, whose name (likely—there’s some debate) comes from Scott’s misreading of the name of an Anglo-Saxon king, Cerdic of Wessex.

Cerdic. Titivillus strikes again.

The subsequent massive popularity of Francis Hodgson Burnett’s spectacularly maudlin (seriously, it’s worth reading for how over the top this thing is) 19th century novel Little Lord Fauntleroy—whose young protagonist is named Cedric Errol—made “Cedric” the “Ryder” of its day, and the world took another step closer to forgetting that poor old Cerdic of Wessex had ever existed in the first place.

4. The Horns of Moses

Is a word spelled wrong if it happens to be spelled the same as the word you wanted to spell in the first place? I believe in my heart that Titivillus counts these homographs towards his quota (the guy has to fill up a thousand sacks a day with these things, remember). And in this case, the damage done by the mistake was both far-reaching and hilarious.

The calamitous series of events leading to Moses’s accidental horns is—as I understand it—related to the fact that the Hebrew word qaran, meaning “to shine,” looks exactly the same as the word qeren, meaning “horn,” when it’s written without vowels (qrn) as would have been the case around the time that the Old Testament was being translated from Hebrew into Latin. As a result, Saint Jerome—whose 4th century Vulgate Bible is truly iconic—rendered Exodus 34:39, which reads, “When Moses came down from Mount Sinai, he did not know that his face was shining,” as:

“When Moses came down from Mount Sinai, he did not know that his face was horned.”

For some centuries, artists depicting the scene (including Michelangelo) took Jerome at his word, and that is how Moses got his horns.

5. The Literary Interruption

Legend has it that when James Joyce was dictating a part of Finnegans Wake to Samuel Beckett, he heard a knock at the door and said, “Come in,” which Beckett dutifully wrote down as part of the text. When Joyce reviewed the passage, he elected to leave the accident as it was. As Joyce biographer Richard Ellman tells it:

Afterwards he read back what he had written and Joyce said, ‘What’s that “Come in”?’ ‘Yes, you said that,’ said Beckett. Joyce thought for a moment, then said, ‘Let it stand.’ He was quite willing to accept coincidence as his collaborator. Beckett was fascinated and thwarted by Joyce’s singular method.

Confounding things somewhat, Finnegans Wake does not have a “Come in” that fits this story, but scholars have found a “What’s that” in an early edition, which could very well be an accidental transcription by Beckett of Joyce reacting to a sound in the room. The relevant passage runs as follows (emphasis mine):

But up tightly in the front, down again loose, drim and drumming on her back and a pop from her whistle whats that. O holytroopers?

Like many an English literature student after him, poor Titivillus must have had an absolutely miserable time with Finnegans Wake, as this anecdote proves. Is it really a typo if the author decides he likes it after all?

6. The Greatest Game

I’ll end with a proper typo, just so Titivillus doesn’t get sore beten when he gets home. It’s from a 2011 football recap in The New Orleans Times-Picayune, and it makes me laugh every time.