FUBAR, SUSFU, and 17 Other Glorious “Military Screw-Up Acronyms”

When the snafu goes fubar and suddenly you have a tuifu on your hands ...

A February 1944 issue of Newsweek magazine has a brief gloss on “The State of the Language” that poses more questions than it gives answers:

Recent additions to the ever-changing lexicon of the armed services:

Fubar: Fouled up beyond all recognition.

Janfu: Joint army-navy foul-up.

Jaafu: Joint Anglo-American foul-up.

“Fubar” is familiar to us alongside “snafu” (Situation Normal: All Fucked Up), and both have had enough linguistic success to achieve the rare Pinnochio-becoming-a-real-boy status of shedding the vulgar majuscules and periods that cling to most acronyms and remind us all of where they came from. But as the Newsweek gloss suggests, these colorful slang words are just the most illustrious members of a large family of terms that did hard work in the trenches cataloguing every conceivable bureaucratic military foul-up without any of the recognition.

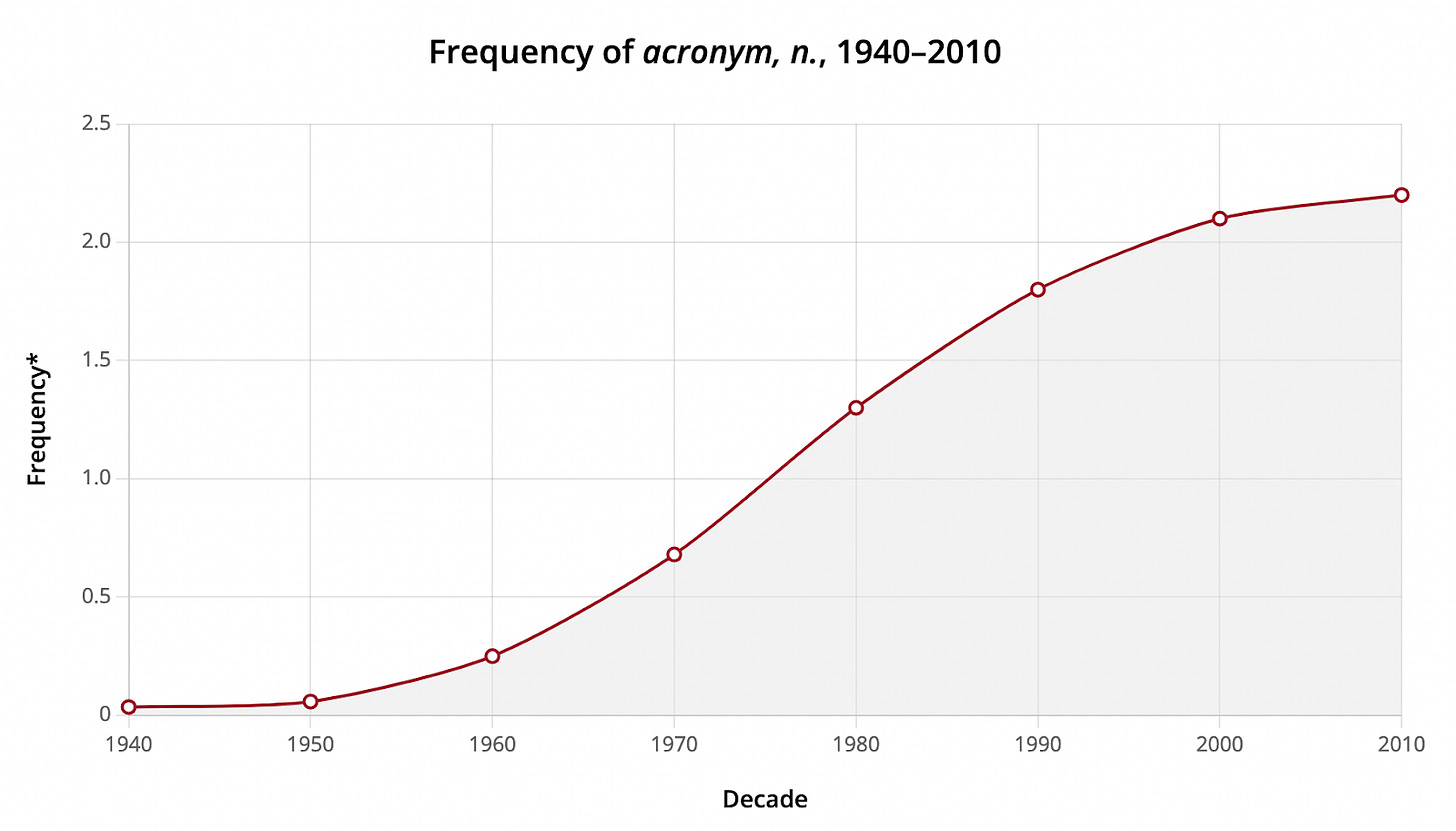

With a good deal of help from Paul Dickson’s marvelously comprehensive War Slang: American Fighting Words & Phrases Since the Civil War, I’ve tracked down a few more of what Dickson calls the “military screw-up acronyms of the SNAFU and FUBAR school of catastrophe” so I can give them their well-earned day in the sun here. There’s a rich history of slang terminology developed during military conflicts and becoming part of civilian lingo, but, as Dickson points out, World War II was “the first war to see the large-scale introduction of initialisms and acronyms.” In fact, the word “acronym” doesn’t get used at all in English until the 1940s, when everybody suddenly decided they liked making words out of initials.

There is something uniquely American about the Military Screw-Up Acronyms. Prior to the acronym mania of the ’40s and ’50s, H.L. Mencken was already remarking on “the characteristic American habit of reducing complex concepts to the starkest abbreviations.”

Thus the American, on his linguistic side, likes to make his language as he goes along, and not all the hard work of his grammar teachers can hold the business back. A novelty loses nothing by the fact that it is a novelty; it rather gains something, and particularly if it meets the national fancy for the terse, the vivid, and, above all, the bold and imaginative.

And while Mencken may have been turning his nose up a bit at this tendency, the terseness, the vividness, and the novelty of MSUAs like “fubar” and “janfu” are quite charming to a modern ear. Given the military context, there’s also a sense of wry humor and shared suffering — an absurdist acceptance of the chaotic — that speaks through coinages like “tarfu” (Things Are Really Fucked Up) and “sapfu” (Surpassing All Previous Fuck-Ups). “What comes through in much of this material,” says Dickson, “is a sense of humor, irony, and comradeship.”

By the end of the Second World War, the taxonomy of fuck-ups was nearly complete: We had words to indicate a standard, more-or-less expected state of catastrophic incompetence, like “susfu” (Situation Unchanged; Still Fucked Up) supplemented by a lexicon for more alarming (but still expected) states of affairs. When the snafu, which seemed to be resolving into a susfu, suddenly went “fubb” (Fucked Up Beyond Belief), you might find yourself staring down the barrel of something “fumtu” (Fucked Up More Than Usual) or — worse — a “tuifu” (The Ultimate In Fuck-Ups).

Whether your janfu was tarfu, your “jacfu” (Joint Anglo-Chinese Fuck-Up) was a susfu, or, God forbid, your jaafu was completely fubar, at least you knew where you stood — somewhere along the natural evolution from a snafu to a tuifu to a susfu, which is really just a snafu plus time.

There have been a few worthy additions to the MSUA corpus since World War II. The Vietnam War gave us “commfu” (Completely Monumental Military Fuck-Up), as well as a couple of acronyms for screw-up-adjacent situations like “wetsu” (We Eat This Shit Up or We Expect This Shit Usually), an expression of exhausted resignation regarding the indignities of daily life, and the rather wonderful “swag” (Scientific Wild-Ass Guess) for the type of informed speculation that tends to lead to a tuifu.

If anything, the MSUA dictionary has become even more crass and direct with its most recent additions, giving us the colorful “bohica” (Bend Over, Here It Comes Again) and the evocative “jafdip” (Just Another Fucking Day In Paradise). Meanwhile, the English have made a persuasive case for the understated expressiveness of “balls-up,” giving the whole concept new life and meaning with “sabu,” “nabu,” and “tabu” (respectively Self-Adjusting-, Non-Adjusting-, and Typical Army Balls Up).

As S.V. Baum points out in a contemporaneous account of the military acronym boom that started in the ’40s — apart from the O.G., snafu, “none of these secondary terms has lasted in the active popular vocabulary, for the parent word has seemed to fill the descriptive need adequately.” Which is probably true, but it’s a shame, because I’d be quite content to while away a quiet afternoon debating whether we’ve found ourselves in a susfu, a tuifu, or a more complex but nonetheless comfortingly familiar sabu.

Reading every use of "swag" as "Scientific Wild-Ass Guess" from now on.