The Weird Grammar Rule We All Obey Without Knowing It

Why you can’t let the beautiful, stupid, big cat in no matter how much she meows at you

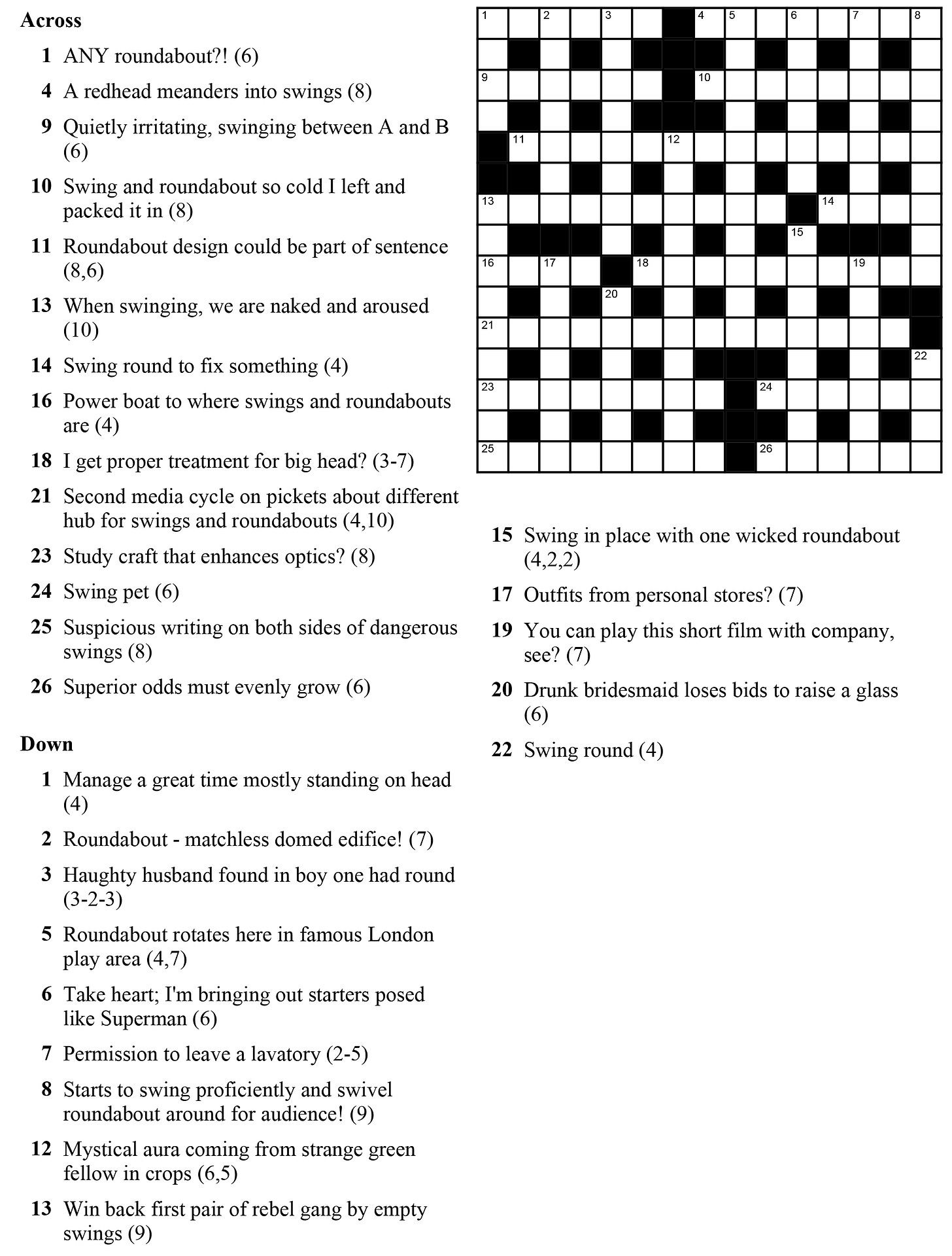

Skip to the end (or click here) for a puzzle I’ve made you. My crash course on how to do cryptic puzzles begins here.

There’s a reason you can’t get a show, American, furry, stripey, round, old, big, stupid cat, and it’s not just because she’ll probably pee in your shoes. The reason (and I should emphasize that it’s not a rule, but more like a language habit) has something to do with what’s called Order Force, which sounds like a directive General Hux might give on Starkiller Base and is only slightly less cool to think about: When we stack adjectives together in English, we tend to do it unconsciously in something like the order that matches number, opinion, size, physical quality, shape, age, color, origin, material, type, purpose. So your five stupid, big, round, old, stripey, furry, American show cats will feel much more at home even if some of them destroy the furniture.

There appears to be some slight disagreement about the specifics of this order, as the above list (which comes from the Cambridge Dictionary) isn’t precisely the same as the list by language-writer Mark Forsyth that occasionally goes viral, but if you test it yourself, you’ll realize that there’s something almost indefinably wrong with concepts like Clifford, the Red, Big Dog; My Greek, Fat, Big Wedding; Angry 12 Men; Riding Little Red Hood; The Budapest Grand Hotel; The Little Brave Toaster; and The Red Thin Line; but The Ugly, The Bad, and The Good is (inferior but) broadly fine — because the former group break the hierarchy in one way or another, while the latter example is just a list of three opinions about Clint Eastwood and his friends.

As Forsyth has observed, there are plenty of exceptions to this “rule.” The most frequently cited example is “Big Bad Wolf,” which goes size, opinion Noun instead of the other way around. Forsyth (and others) argue that this is because of another batshit-crazy-but-once-you-think-about-it-deeply-intuitive rule called ablaut reduplication, which decrees that when we make repetitive sounds, we tend to put i-sounds before a-sounds or o-sounds, hence: chit-chat, mishmash, tip-top, singsong, crisscross, tick-tock, dilly-dally, ding-dong, and riff-raff and not chat-chit, tock-tick, crosscriss, and other such abominations. But I would argue that “Big Stupid Wolf,” “Big Disreputable Wolf,” and “Big Mean-Spirited Wolf” taste broadly fine in my mouth even though they don’t involve reduplication, so I’m more inclined to agree with linguist Simon Horobin, who cites this as an example of the Pollyanna Principle, “by which speakers prefer to present positive, or indifferent, values before negative ones.”

Horobin also points out that English speakers prefer not to put more than three adjectives before a noun (so we’d be more inclined to say something like “my big round stripey cat who is stupid and furry” than string all those qualifiers together in a row), and that we have nuanced preferences for adjective-ordering that aren’t explained by Order Force (“Long, Tall Sally” but not “Tall, Long Sally” even though long and tall are both about size, for instance). Other factors, like how subjective or indeed how “nouny” an adjective is (“red” can be used as a noun in certain cases, unlike “mean-spirited”) can muddy the waters as well, but it is true that English speakers have a strange, intuitive sense for where an adjective ought to go in a list and cats are objectively wonderful even when they’re also stupid, big, and furry and pee in your shoes.

I have made you a puzzle. The puzzle image is below if you want to print it out like our forebears used to, but you can also fill it in with a click!

Flawless. Well done.

I love seeing the profound, deep, and usually unarticulated brought to the level of conscious discourse. Thank you!