What to Do When You’ve “Got the Morbs”

“Got the morbs” shows up to delight us every couple of years, but the dictionary where it comes from is a treasure trove.

James Redding Ware was a 19th century British novelist best known for creating (pseudonymously, as Andrew Forrester) one of the first female detectives in fiction — the mysterious Miss G — who bursts onto the scene in the rather unsubtly titled The Female Detective. Miss G (sometimes called Miss Gladden) was making brilliant deductions from far too little evidence more than 40 years before Sherlock Holmes got his start in A Study in Scarlet and almost 70 years before the first Miss Marple novel, The Murder at the Vicarage, which makes Ware an important early figure in the relatively short history of detective fiction. But nowadays, Ware is far better known for a single 11-word entry in his final piece of writing, a posthumously published dictionary of Victorian London slang called Passing English of the Victorian Era:

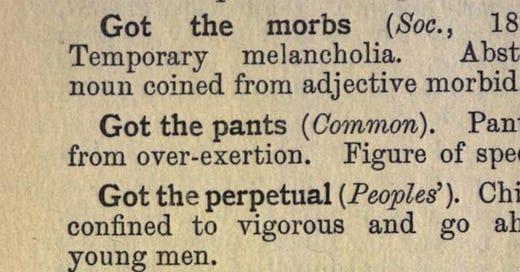

Got the morbs - Temporary melancholia. Abstract noun coined from adjective morbid.

The revelation that some number of gloomy Victorians were trudging around in dingy London back alleys complaining of “the morbs” is so delightfully on the nose that this passage goes viral every couple of years when Ware’s dictionary is rediscovered. As well as being a rather magnificent turn of phrase for a common ailment, it has something of a contemporary sound to it, which makes it feel more like a modern coinage from a steampunk novel, or a clever Tumblr parody, than a real-ass thing that cool, disaffected teens might have said to one another in Clapham Common in 1909.

As marvelous as it is, the only real downside of the morbs is that it tends to overshadow everything else in Ware’s dictionary, which is a treasure trove. Morbs, for instance, are not the only thing you might get in Victorian London — Ware has entries for Got the pants (being out of breath), Got a collar on (being stuck up), Got the glow (blushing), Got the shutters up (being surly), Got the perpetual (being a vigorous and “go-ahead” young man, which is probably quite nice but sounds rather tiring for the rest of us), and Got the woefuls (the very next stop on the cursed subway line that starts with the morbs).

Passing English is also a bonanza of colorful vocabulary for the creatively drunk that rivals even Ben Franklin’s Drunkard’s Dictionary in its variety. One might be Arfarfanarf after consuming multiple half pints of ale, Be-argered, which is drunk and argumentative, or Bang through the elephant, a sort of cockney rhyming slang (an elephant’s “trunk” rhymes with “drunk”) that Ware defines rather charmingly as “a finished course of dissipation.” Alongside the Boiled owl (slang for a drunkard that one of Ware’s sources tut-tuts as “a gross libel upon a highly respectable teetotal bird which, even in its unboiled state, drinks nothing stronger than rain-water”) the nicest of all is Altogethery, which is a sloppy, loungey step on the road to completely addled that actually turns up in an 1815 letter by Lord Byron:

"Like other parties of its kind, it was first silent then talky, then argumentative, then disputatious, then unintelligible, then altogethery, then inarticulate, and then drunk."

Unless you were a Balloon Juice Lowerer (teetotaler), you were in constant danger, in Ware’s London, of Playing camels (putting away more than you need) with a case of Bellywengins (bad beer) and ending up with a pair of Monday mice (black eyes from a hangover after a bang-through-the-elephant weekend).

On the plus side, just the right amount of bellywengins (a corruption of “belly vengeance”) might give you the courage to tell people what you really think of them: Ware’s dictionary is chock-full of glorious insults like Barber’s cat (a skinny man), Cabbage garden patriots (meaning “cowards,” in reference to an Irish insurrection that ended ignominiously in a cabbage patch), Enthuzimuzzy (a mocking reference to an embarrassing enthusiasm), Muffin wallopers (scandalmongers, presumably because they enjoyed their salacious gossip with some delicious baked goods), and Gigglemug (simpering).

The whole thing is, to borrow another entry from Ware’s dictionary, Nanty narking (great fun); it palpitates with actuality (reflects life with all its variety); it is veritably some pumpkins (the delightful opposite of “small potatoes”) — and it’s a fantastic cure for a nasty case of the morbs.

Lovely piece. I find it refreshing to remember that we have always played with language, and what fun that is.

I love this! Immediately adopting “got a collar on”!