5 Preposterous Words That Wordle Will Actually Accept as Valid

New starter word: "Sloom." They can't stop you!

A brief programming note – I’ve paused paid subscriptions during this last hiatus and will plan to do that any time work gets in the way of putting this newsletter out – but I’m hopeful we can settle back into a more regular cadence starting this month and will eventually turn things back on again if so. Say a prayer for my time-management skills!

Deep in the cavernous basements of The New York Times, where the conniving fatcats of the Wordle team spend their days plotting new ways to spin letters into gold, there is a giant horde of 5-letter words so precious and so dangerous that to lay eyes on it, even for a second, would be a death sentence. I’m assuming. But thanks to the dedication and bravery of the Wordle Resistance (at present this is just me, but I’m actively recruiting), some dozens of these highly bankable pentagrams (OED assures me that pentagram can mean “five-letter word” as well as the other thing) can be seen and enjoyed by the worthy public, away from the prying eyes of the jackbooted Wordle police.

It is through these efforts that I have discovered something quite remarkable: For every BLAND, STALE, EMPTY, or other such flavorless provender that Wordle’s black-eyed puzzle dispensers delight in spooning into our meagre bowls when it’s time to dole out our daily Wordle slop, there are a hundred five-letter miracles in the Wordle vault so bright and so dazzling that it’s a wonder they don’t burn the whole thing down. Here, for the first time, are just a few of those precious five-headed beasts. Try one, next time you sit down to a Wordle. The joyless apparatchiks of the Wordle High Command will grudgingly let them through, but I guarantee they’ll never be the answer.

“Fubsy” is, as the young people say, having a moment. “I’m in my ‘fubsy’ era,” they are surely also saying. Taylor Swift is no doubt this very second composing a billion dollar tune about a fubsy heroine who poisons her husband and drives off in a cheeky little sports car. But what’s my evidence for this, you’re wondering? Well, not only did Stephen Fry publicly go to bat for “fubsy” in a 2009 campaign to bring back obscure words, but this little-pentagram-that-could had a glamorous cameo appearance in the 2018 bestseller Where the Crawdads Sing (which also significantly raised the profile of crawdads,1 who have never had very much to hang their tiny little hats on):

Bald and fubsy, his coat buttoned tight against a round belly, Mr. Lang Furlough testified that he owned and operated the Three Mountains Motel in Greenville.

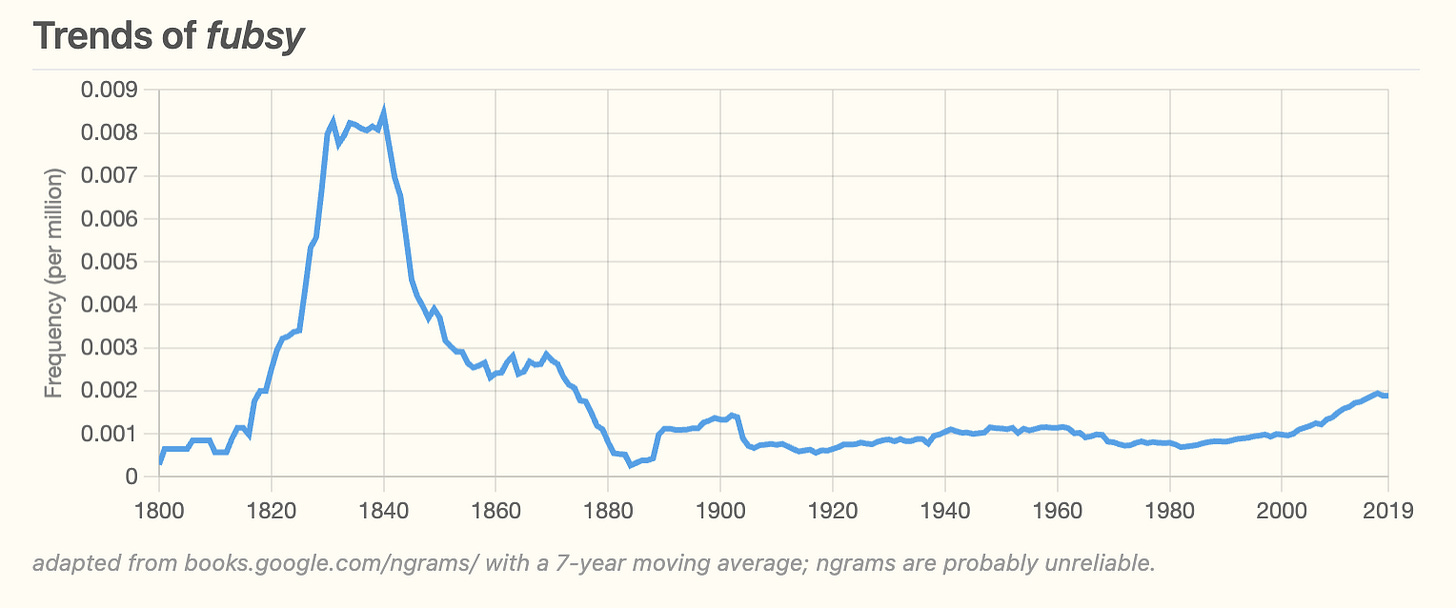

You can see what I’m calling the “Crawdad Bump” in this chart from etymonline, which I am aware also raises some very interesting questions about what “fubsy” did in 1840 to cheese off everyone in the entire world apparently.

But and so what all does “fubsy” mean?, everyone is politely and patiently asking. Well, everyone will no doubt be satisfied to learn that fubsy is the adjectival form of the fully obsolete fubs. As in the following passage from John Crowne’s mostly forgotten Restoration comedy Sir Courtly Nice: Or, It Cannot Be:

A very honest Gentleman, but very much addicted to Marriage; ’tis he that I told you is to marry my Indian Fubs of a sister.

“Fubs” (a person who is squat and chubby) was also a pet name given by King Charles II to his mistress the Duchess of Portsmouth (real charmer, this guy) and the actual name of his yacht.

Meaning: Squat and chubby, but in an endearing kind of way like you would say to your mistress or your yacht.

Origin: Via the obsolete “fubs,” by suggestion from words like “full” and “chub.”

Wordle’s view: This is all far too interesting. Let’s just do “SLATE” again and see if anyone notices.

I like voulu because it is one of those rare words that is what it does, which is to say that it means “labored and contrived” and it is absolutely impossible to use without sounding so. The earliest occurrence of voulu as an English word is in the following passage from E. Nesbit’s Daphne in Fitzroy Street:

“After all,” Seddon was saying, as the perfect satellite began to revolve in his orbit, laden with choice hors d'oeuvres, “perhaps there's something more delicate, less voulu, in our little dinner as it is. The poignant beauty of the incomplete.”

I’ll pause here just to give you two conflicting pieces of writing advice which are that 1) If E. Nesbit invented “voulu,” then it must be a good word to use, and 2) people will think you are a real piece of work if you try to use it, and you absolutely shouldn’t. God knows I’ve tried.

Meaning: Contrived, deliberate, labored.

Origin: From the past participle of the French vouloir, meaning “wanted”

Wordle’s view: We prefer not to use words that contain the letter “u” — it’s a far too exciting vowel.

Vampires are so over. Next time a vampire tries to bite you, don’t give them the satisfaction of screaming or fainting. Just look disappointed and say, “Oh, I was hoping for a lamia.” In Greek mythology, Lamia (Λάμια) was a Libyan queen who, according to some accounts, made the mistake of being attractive to Zeus, which caused Hera to murder her children. Understandably upset about the situation, Lamia (less understandably) decided to start eating other people’s kids and drinking their blood. Zeus, feeling very bad about the whole thing, gave Lamia the power “of taking her eyes out of her head, and putting them in again,” which, far be it from me to be critical of a deity, but I don’t think this was constructive.

The extremely creepy eyes detail shows up in various accounts by Greek historians who tend to mention it without providing much more context as Plutarch does in his essay De Curiositate (“On Being a Busybody”), bringing the same enthusiasm you’d expect from a description of the proper way to store contact lenses:

But as it is, like the Lamia in the fable, who, they say, when at home sleeps in blindness with her eyes stored away in a jar, but when she goes abroad puts in her eyes and can see, so each one of us, in our dealings with others abroad, puts his meddlesomeness, like an eye, into his maliciousness.2

Outside of the context of this particular myth, the lamia had a more generic role in antiquity as a bugaboo for children — “Eat your broccoli, Clitus, or the lamia will devour you whole and feast on your blood.” Strabo refers to this time-honored parenting technique in his first century Geographica:

[We] relate to children pleasing tales to incite them [to any course] of action, and frightful ones to deter them, such as those of Lamia, Gorgo, Ephialtes, and Mormolyca.

As far as I can tell, this more generic lamia is due to the etymological associations with the Greek λαμυρός (lamuros), which means “gluttonous” and is related to the English larynx. Some sources also connect the word to lemur, because lemurs (as I’ve written about before) are actually scary and wicked despite their cute, furry faces. By the second century AD (most notably in Philostratus’s Life of Apollonius of Tyana) Lamiae get a new origin story as serpents transformed into witches, and — having expanded their horizons beyond children — are swanning about seducing men and devouring them, a tendency which Keats somehow manages to make rather swoony and romantic in his 1819 poem Lamia:

Then Lamia breath’d death breath; the sophist's eye,

Like a sharp spear, went through her utterly,

Keen, cruel, perceant, stinging: she, as well

As her weak hand could any meaning tell,

Motion'd him to be silent; vainly so,

He look'd and look'd again a level—No!

“A Serpent!” echoed he; no sooner said,

Than with a frightful scream she vanished

Lamia is also a kind of flatfish and a species of owl, both of which are considerably nicer things to think about.

Meaning: A demony, serpenty lady who drinks children’s blood and eats men whole, which we simply cannot endorse here even in cases where it’s deserved.

Origin: Greek λαμυρός, meaning “gluttonous”

Wordle’s view: TOO SCARY. But we’re confident we can achieve roughly the same effect with today’s word, “BITEY.”

A gleek is a jest or a trick, as in, “It was just a gleek, man! Don’t be such a lamia!” There’s an awful lot of dignified hedging in the OED about where exactly the word comes from, but it’s probably related to “glee” and therefore my personal favorite (don’t ask) Proto-Indo-European root *ghel-, which means “to shine” and which gives us a truly astonishing array of words including yellow, green, glance, glide, gloat, glitter, melancholy(?!), and glib. In fact, if you ever see a “gl-” word like “glow,” “gleam,” “glass,” or I guess “gleek” in the wild, there’s a very strong chance that *ghel- is its daddy.

Meaning: A gibe, a jest, a trick, or (more rarely), a coquettish look

Origin: Really looks like it’s a diminutive form of “glee” — not sure why the OED won’t just come out and say it

Wordle’s view: You’ve got to be gleeking us. Today’s word is “TIRED.”

Speaking of “tired,” sloom is a truly precious and magical word that means “to have a little sleep,” as in what I intend to do right now, thank you very much. See you next week hopefully!

“Crawdad” is an inherently funny word to say, as is the equivalent “crawdaddy.” Without, hopefully, ruining the fun, I’ll note that the “dad” is a bit of an accident - it was originally “crawdab” from “craw” (which, like “crab” is related to “crevice,” where they hang out) and “dab,” meaning “a moist, flattish mass.” None of this can be very pleasant to hear if you happen to be a self-respecting crawdaddy.

Not to rag on Plutarch, who is genuinely a stand-up guy, but it’s extremely funny to me that he was sitting at his desk trying to figure out the best way to talk about the classic human behavior of “putting our meddlesomeness into our maliciousness when dealing with foreigners,” when he suddenly remembered that the Lamia keeps her eyes in a jar and was like, “Aha! The perfect metaphor for this!”

Surely Gleek had a resurgence when the Glee fandom chose that as their collective noun

What a joy it is to read tongue in cheek faux-snark that actually works. So many writers just give up and sound bitter. Much appreciated!