The Absolutely Ridiculous History of Palindromes

And why they threw the first palindromist into the ocean

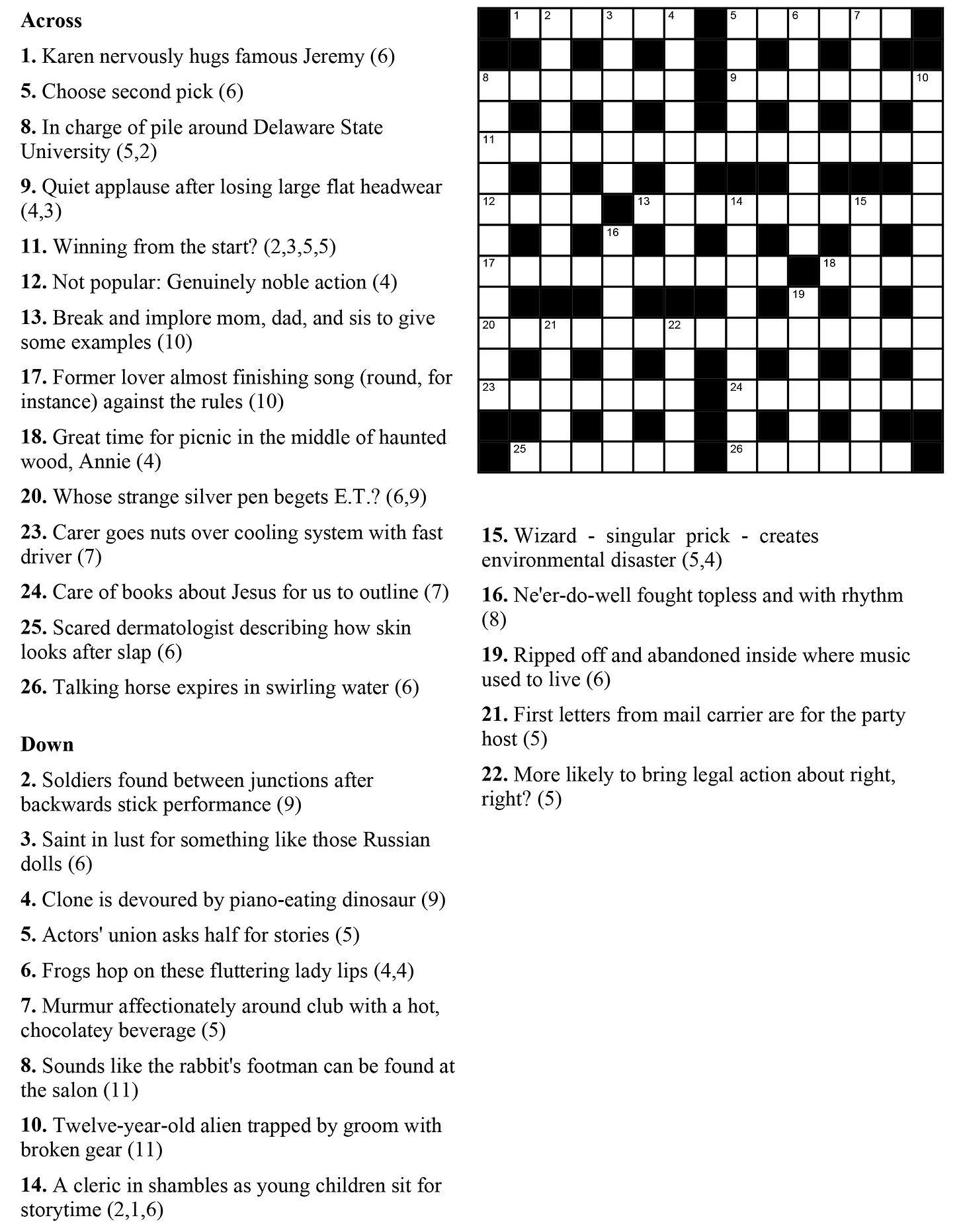

Skip to the end for a puzzle. My crash course on how to do cryptic puzzles begins here, and you can find puzzle solutions and explanations here.

In 1986, a writer in St. Augustine, Florida, named Lawrence Levine published a 167-page novel that reads the same backwards as it does forwards. Its palindromic title was Dr. Awkward & Olson in Oslo, and it tells the story of a bumbling private eye named Sam X. Xmas battling the evil Dr. Awkward with the help of the noble Olson (in Oslo) and various palindromic characters such as Mabel E. Bam, Evita Dative, and Emil S. Slime. At 31,594 words, it is almost certainly the longest known palindrome. And like all things palindrome the main thing that it is apart from being a palindrome is hopelessly silly.

Which is not to take anything away from Lawrence Levine’s achievement. It’s just to say that palindromes — even the most impressive ones — have always been a bit of a novelty act. The earliest reference to a palindrome that I can find bears this out: It’s an absolutely vicious diss track by the Roman epigrammatist Martial from the 1st Century AD called “To Classicus, in Disparagement of Difficult Poetic Trifles.” It goes like this:

Because I neither delight in verse that may be read backwards, nor reverse the effeminate Sotades; because nowhere in my writings, as in those of the Greeks, are to be found echoing verses, and the handsome Attis does not dictate to me a soft and enervated Galliambic strain; I am not on that account, Classicus, so very bad a poet. What if you were to order Ladas against his will to mount the narrow ridge of the petaurum? It is absurd to make one's amusements difficult; and labour expended on follies is childish. Let Palaemon write verses for admiring crowds. I would rather please select ears.1

Mic drop! Martial is probably referring to “metrical palindromes” (a type of palindrome wherein the poem retains the same meter when read backwards), but the sneering reference is enough to have obtained for Sotades the almost certainly undeserved credit of being the palindrome’s inventor. Which is fortunate for Sotades’ reputation, as he’s otherwise known as Sotades the Obscene, thanks to some genuinely filthy verse that got him “sealed up in a lead coffin and thrown into the sea.”2

Martial’s withering review notwithstanding, palindromes get a little bit of heat over the next few centuries thanks to the popularity of the Sator Square, a five-word palindrome that reads the same up, down, and across.

If you’ve seen the movie Tenet, it’s full of references to the Sator Square (right up to the film’s title, which is the central word of the Sator palindrome), and it makes about as much sense — the Latin phrase, “Sator Arepo tenet opera rotas,” means something like “The farmer Arepo has the wheels as his labors.” Like Tenet, the ~vibes~ of the Sator Square were much more relevant than its actual meaning, and — along with other palindromic incantations — it tends to get used in magical contexts throughout history, as a ward or a healing spell.

It’s not much of an exaggeration to say that between the first appearance of the Sator Square (the earliest one we have was found in Pompeii’s less famous but equally volcanoed neighbor Herculaneum, so roughly 79 A.D.) and “A man, a plan, a canal, Panama” (created in 1948 by British wordsmith Leigh Mercer), there’s only one truly kickass palindrome, the Medieval Latin riddle “In girum imus nocte et consumimur igni,” which translates as “In a circle we go at night and are consumed by fire.” The solution: “moths.”

After Leigh Mercer, the most famous modern palindromist is probably comedian Demetri Martin, who used to talk about a 224-word palindrome he wrote in college during a segment in his act devoted to “useless talents.” You can read the whole thing here, but it begins like this:

Dammit I'm mad

Evil is a deed as I live.

God, am I reviled?

As with other attempts at genuinely long palindromes, there’s fun to be had in trying to wring some meaning out of it, but the pleasure in reading comes primarily from appreciating the sweat and virtuosity required to create it. The first extended palindrome by Lawrence Levine (of Dr. Awkward & Olson in Oslo fame) is even more satisfying in that regard, bringing to mind a sort of terminally dorky Eminem with its driving rhythm, verbal fireworks, and almost desperate momentum. “So Do Dodos,” as it’s called, is 170 words long, and it begins like this:

Tacit, I hate gas,

(aroma of evil), a nut, sleep,

no me Ions, drawers, bards,

Eta Delta, ebon, a hare, macaroni,

stone raps, id, a lass lion,

apses, ore, lines, a loner, war

oh, bait I hate! - jam, ugh;

cabs, warts too, spas, Odin, roes.

This does not exactly evoke the contemplative mystical power of the Sator Square, or even the potential for meaning and revelation promised by Christopher Nolan’s palindromic Tenet, but it fits with the good-natured, fun-loving ethos of modern palindromists, who meet semi-regularly to battle one another at the World Palindrome Championships (hosted by the world’s only crossword celebrity, Will Shortz), a competition where you can only excel if you are equal parts brilliant and absurd. Which is a pretty good combination of traits, unless you’re Sotades (the Obscene), whose palindromes were so incendiary that they pushed him into the sea.3

I’ve made you a puzzle. See if you can spot the palindromic theme words. The puzzle image is below if you want to print it out like our forebears used to, but you can also fill it in with a click! (The solution is explained and annotated here.)

Martial, Epigram LXIX

The Rise and Fall of Alexandria, by Justin Pollard and Howard Reid