Those of us who aspire to a quiet life know that (in polite company) we should never raise the topics of politics, religion, or whether it’s advisable to deploy an extraneous comma before “and” or “or” in a series of three or more terms. The question of the Serial Comma—known to pedants as the “Oxford Comma,” and to delusional Harvard pedants as the “Harvard Comma”—has been the source of more enthusiastic bomb-throwing amongst the grammatically inclined than almost any other topic (with the possible exception of what-all we ought to be doing w/r/t “irregardless”).

In 1940, the journal American Speech surveyed the state of the Oxford Comma Wars in an article entitled “The Serial Comma before ‘And’ and ‘Or’,” by R. J. McCutcheon, who—even then—was aware of the passions inflamed by his topic.

The rule of punctuation calling for a comma before and or or joining the last two members of a series, may seem the most unimportant subject in the world but I have found such strong opinions for and against its application that I am presenting some of my findings.

McCutcheon’s article—which surveys various newspaper copy desks for their opinions on the matter—contains an early example of the argument favored by opponents of the Serial Comma (let’s call them Serial Killers) that “and” and “or” essentially are commas, rendering the Serial Comma not just gratuitous, but redundant. Says one committed Serial Killer:

‘It has been found that much of the nicely logical but "fussy" punctuation developed by the more pedantic is not necessary to clearness, and as a result the modern newspaper gets along very well with about half the volume of points used in book composition.’

You can almost hear the strenuous clacking of the typewriter and the grinding teeth behind the thin-lipped smile in this response, which is doubly amusing when it’s weighed against a politely opposite viewpoint from someone on the other side of the copy desk:

So far as the editorial pages of The Sun and The Evening Sun are concerned, there is considerably more latitude in matters of punctuation, but the latitude doesn't seem to extend far enough to include this particular rule. I can recall, now that I think of it, occasions on which I wanted very much to use a comma between C and D, and had to spend most of the day struggling with compositors, proof readers and various other people in order to get my way.

The Serial Comma has been used in English writing since the Renaissance, but its discovery (as it were)—and its emergence as the “Oxford Comma”—are generally attributed to the British indexer F. H. Collins, with an assist from the philosopher Herbert Spencer (who also, incidentally, coined the term “survival of the fittest,” which, I dunno … what a legacy!). Collins’s influential usage guide, Authors’ and Printers’ Dictionary, was published by the Oxford University Press (hence “Oxford Comma”) in 1905, and cited Spencer in its justification for the extra bit of punctuation:

The late Herbert Spencer allowed me to quote from his letter : — “ whether to write ‘black, white, and green,’ with the comma after white, or to leave out the comma and write 'black, white and green’ — I very positively decide in favour of the first. To me the comma is of value as marking out the component elements of a thought, and where any set of components of a thought are of equal value, they should be punctuated in printing and in speech equally: Evidently therefore in this case, inasmuch as when enumerating these colours black, white, and green, the white is just as much to be emphasized as the other two, it needs the pause after it just as much as the black does.”

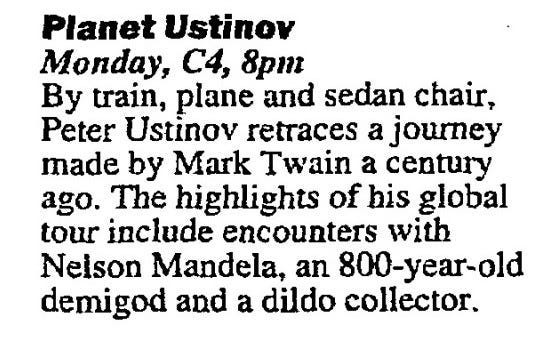

More than a hundred years after Spencer’s thoughtful advocacy for the Serial Comma, a poll run by FiveThirtyEight and SurveyMonkey found that 57 percent of respondents agreed with him, compared to 43 percent who preferred to do without it. The argument most commonly cited by modern Spencerites is that a Serial Comma avoids the ambiguity that occurs in the following (frankly unhinged) book dedication:

“To my parents, Ayn Rand and God.”

But the Serial Killers are quick to point out that you can achieve an equally vexing ambiguity with the following dedication:

“To my mother, Ayn Rand, and God.”

In both cases, the initial comma can be misread as introducing an appositive rather than preceding a new item in the series, leading readers to think the author is claiming to have been raised by Ayn Rand, who—in point of fact—preferred writing some of the world’s heaviest books to the subtle joys and trials of parenthood.

To press the Serial Killer position a bit further, there’s an argument to be made that if the goal is to use punctuation only when it’s necessary to support meaning, one ought to proceed from the position of doing without the extra comma and either using it in the rare events where clarification is needed, or simply rearranging the sentence to do away with any ambiguity: To God, Ayn Rand and my parents. (This line of reasoning would also protect the SKs from having to defend their philosophy vis à vis the multimillion dollar 2014 lawsuit that hung on the lack of a Serial Comma in the phrase “The canning, processing, preserving, freezing, drying, marketing, storing, packing for shipment or distribution of [agricultural products].”)

But this line of attack doesn’t answer Spencer’s original point about the Serial Comma, which is about weight and rhythm in a sentence. Those of us who are particularly prone to subvocalization when reading will notice that a comma suggests a rhythmic pause that an “and” does not—something that’s particularly apparent when you’re faced with a series that itself contains a subordinate series, as in:

When deciding on an appropriate dedication for your book, it’s always best to confine yourself to one of the five following options: your cat, your parents, the philosopher Herbert Spencer, Ayn Rand and God, or your loving partner.

I find that I mentally tap the brakes after each comma in the series, but not before a comma-less “and,” which is good and proper in this case, but jarring when the “and” is supposed to be doing the same job as the commas in the series. As Spencer says, “when enumerating these colours black, white, and green, the white is just as much to be emphasized as the other two, it needs the pause after it just as much as the black does.”

Although it’s not really an argument pro or con, the Oxford Comma does have one more extremely unlikely ally in the form of R. M. Bevensee, an Assistant Professor of Electrical Engineering at Berkeley, who wrote the actual dedication that (presumably) inspired the apocryphal “Ayn Rand” examples. His 1964 book Electromagnetic Slow Wave Systems begins with a series of three terms, each set off with a comma, including after the penultimate item in the series and before the coordinating conjunction (aka, a classic Serial Comma): “This Book is Dedicated to my parents, Ayn Rand, and the glory of GOD.”

I’m not entirely sure where that leaves us in the Oxford Comma Wars. But hopefully we can all at least agree that the arsonists who insist on two spaces after a period should be drummed out of society and abandoned on an island to contemplate their crimes for eternity.

This article had multiple guffaw-out-loud moments for a grammar geek like me 😂😂😂

"But hopefully we can all at least agree that the arsonists who insist on two spaces after a period should be drummed out of society and abandoned on an island to contemplate their crimes for eternity. "

I wholeheartedly concur with this sentence, Jack, in both senses of the word.

I also believe serial killers of the AP variety belong with their ilk as use of the Oxford comma distinguishes the civilized from philistines, newspaper editors, and ambiguity-spreading barbarians. [Okay, I admit “newspaper editors” could work as an appositive here, but either interpretation works for me.]

Was just discussing this yesterday and said this:

I use it only when it’s ambiguous as to whether the ‘and’ belongs to the item or the list

(Usually longer lists with unwieldy multi-word items)

As for Ayn Rand, sometimes you’ve just got to reorder your lists