It’s widely known that those incurable squares over at Wordle have never had a minute of fun in their entire lives. This is why Wordlebot (the New York Times’s constipated bureaucrat of a Wordle analyzer) recommends that prospective Wordlers choose their starter words from the feckless trio of CRANE, SLATE, and CRATE — respectively, history’s dullest long-necked bird, a tablet that old, dead people used to do their Geometry homework on, and a box to store all your dreams of color and light in the attic where they can’t get out.

Wordlebot gives each of these soporific dullards a 99 out of a possible 99 points if you use it as a starter (how convenient that Wordlebot’s own favorite words to open with should garner such a high score!), and if your goal is to please the moth-eaten automatons who staff the Wordle desk of the New York Times, you’d better paint within the rigid lines that they’ve laid out for you or prepare to suffer the consequences. But if you are willing to shun the prudish dogma of the Wordle intelligentsia and bask in the light of nature, a whole glorious world of illicit five-letter starter words will be revealed to you, and you can soar on their exquisite currents like a scarlet ibis (history’s most interesting long-necked bird) and dance the Wordle dance of the gods. Here are 11 starter words that’ll really tick Wordlebot off.

One of the three things that a nixie can be is a Germanic water sprite, which is already quite interesting. The folkloric nixie has a human top and a fish bottom much like Princess Ariel does, and it lures people into the water for the purpose of drowning them, much like Princess Ariel presumably doesn’t, though I can’t say for sure until I watch The Little Mermaid II: Return to the Sea. The word was first introduced into English by Sir Walter Scott in the following passage from his Waverly novel, The Antiquary, which raises a lot more troubling questions about an entity called the Oak-King than it answers:

“Why performed in such a solitude, and by what class of choristers, were questions which the terrified imagination of the adept, stirred with all the German superstitions of nixies, oak-kings, wer-wolves, hobgoblins, black spirits and white, blue spirits and grey, durst not even attempt to solve.”

Via a different etymology, “nixie” can also mean “a letter whose address cannot be determined by the postal service due to bad handwriting,” and it has a related, obsolete adverbial form that means something like, “emphatically not.” This means, rather satisfyingly, that you can write a coherent but sad short story about a doomed romance between a German mermaid with bad handwriting and a British fairy with pointed ears that goes, “Did the nixie’s nixie reach the pixie? Nixie.”

Wordlebot respectfully1 thinks that NIXIE is a bad starter word.

In a stunning repudiation to those of us who’ve been describing things that look like the letter “H” as “aitchey,” there is an actual word that means “in the shape of the letter H,” and it is “zygal.” It comes to us via the Greek ζυγόν, which means “yoke” (a vaguely H-shaped contraption) and it shares its earliest origins with a root that gives us (through the Latin) “join” and “conjugal,” and (by way of Sanskrit) “yoga.” Wordlebot gives it a D+.

In addition to providing an absolutely choice rhyme for “zygal” in the event that you’re writing an inscrutably lewd poem, “pygal” has the exquisite good judgment to mean “of, relating to, or in the region of the buttocks.” This is, naturally, very funny. It comes to us from the Greek πυγή, meaning “rump,” which also gives us the marvelous “callipygian” (nice-buttocked) and the slightly unwieldy “pygophilous” (buttock-besmitten). Wordlebot, surprisingly, doesn’t hate it!

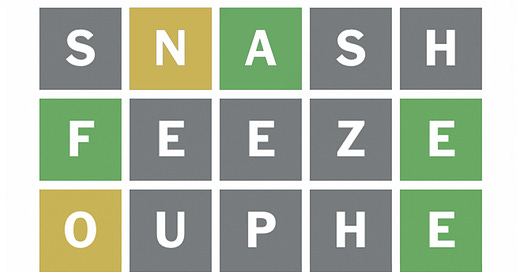

“Snash” means “insolence,” as in “enough of your snash, Wordlebot.” But as a verb, it means (likely onomatopoeically) “biting at hastily or noisily,” giving us the breathtakingly good Scots word for sweets and pastries, “snashters,” inspired by an equally wonderful Middle Low German word “snascherie,” meaning “the eating of dainties.”

Wordlebot says, fine, whatever.

“Mivvy” is an early 20th century British slang word likely derived from “marvel,” and it means “expert,” as in “I’m pretty mivvy at the Wordle.” I’ve included it here because it really cheeses Wordlebot off.

An “ouphe” is another word for an elf, a goblin, or, more specifically a goblin changeling like my 6-year-old (I suspect). Shakespeare is rather fond of ouphes, and they show up in a decidedly bonkers but ultimately successful plot to trick Falstaff in Merry Wives of Windsor:

Nan Page my daughter and my little son

And three or four more of their growth we'll dress

Like urchins, ouphes and fairies, green and white,

With rounds of waxen tapers on their heads,

And rattles in their hands.

Interestingly, this is the direct origin of the common “oaf” and “oafish.” Wordlebot is too exhausted to complain about it.

Despite what will prove to be a truly abysmal Wordlebot score, “feeze” is a gem of a word. Via the Old English fésian, “to drive away,” it has a few related meanings that are all quite lovely. As a verb, it can mean “to frighten or alarm” like its close (and more familiar) relative “faze,” but for a brief, glorious period in the early 19th century, one could be in a feeze, meaning “in a state of alarm,” as in this vertigo-inducing passage from the 1825 historical novel Brother John, or The New Englanders, by John Neal.

‘By Snum! ; but you’re a precious fellow! — in a feeze , I dare say, at receiving a decent letter, from your sweetheart. Zounds!’

More charmingly still, up until 1675, a “feeze” meant something like “that short little run that you take before doing a great big jump,” which sounds very sweet and wholesome until you see it deployed in this extremely threatening letter quoted in Edmund Campion’s 1571 History of Ireland:

“Be thou sure I had rather in this quarrell die thine enemy, then live thy partner : for the kindnes you proffer mee, and good love in the end of your letter, the best way I can purpose to requite, that is, in advising you though you have fetched your feaze, yet to looke well ere you leape over.”

Wordlebot hates it.

“Dorty” is a charming little word that means “sulky” or “pettish.” It sounds like it’s going to be related to “dirty,” but it’s actually from a Scots word, “dort,” meaning “a sulk” or “a huff,” which tends to show up in the phrase “in the dorts,” (“in a sulk”), or joined with the name “Meg” as an epithet for a sulky lady, as in Allan Ramsay’s 1725 play, The Gentle Shepherd:

Then fare ye well, Meg Dorts, and e'en's ye like,

I careless cry'd, and lap in o'er the dike.

You can really grab Wordlebot’s attention with this one, but it still thinks you should have picked CRANE.

To “troat” means, very specifically, “to cry out like a rutting buck,” which is very useful if you know someone who does this, because you can roll your eyes and say to yourself, “He’s in a feeze, troating and snashing like a dorty ouphe” — a fantastically bracing thing to say to oneself.

Wordlebot likes “troat” more than any other word on this list. 🤷

A “quink” is usually defined as “the common brant,” which is decidedly unhelpful of it. In fact, the only thing that could be more unhelpful than defining a “quink” as “the common brant” would be defining a “runch” as “the jointed charlock.”

Wordlebot wants you to rethink your life and your choices.

The jointed charlock.

Wordlebot respectfully requests to be left alone with its thoughts.

True to its insipid nature, Wordlebot is unfailingly polite even when it clearly hates your guts, so for the next few entries after this one, I’ll read between the lines and provide a rough translation of the brief analysis it appends to the score.

Top marks from me for all of these if not from Wordle. Enjoyed this immensely, thank you.

Good to laugh at those 'bots!